It’s the start of a new school year here in North America. We are into the second week of classes and already I am hearing from administrators in both K-12 and higher education institutions who are frustrated with educators who have turned to ChatGPT and other publicly-available Gen AI apps to help them assess student learning.

Although customized AI apps designed specifically to assist with the assessment of student learning already exist, many educators do not yet have access to such tools. Instead, I am hearing about educators turning to large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT to help them provide formative or summative assessment of students’ work. There are some good reasons not to avoid using ChatGPT or other LLMs to assess student learning.

I expect that not everyone will agree with these points, please take them with the spirit in which they are intended, which to provide guidance on ethical ways to teach, learn, and assess students’ work.

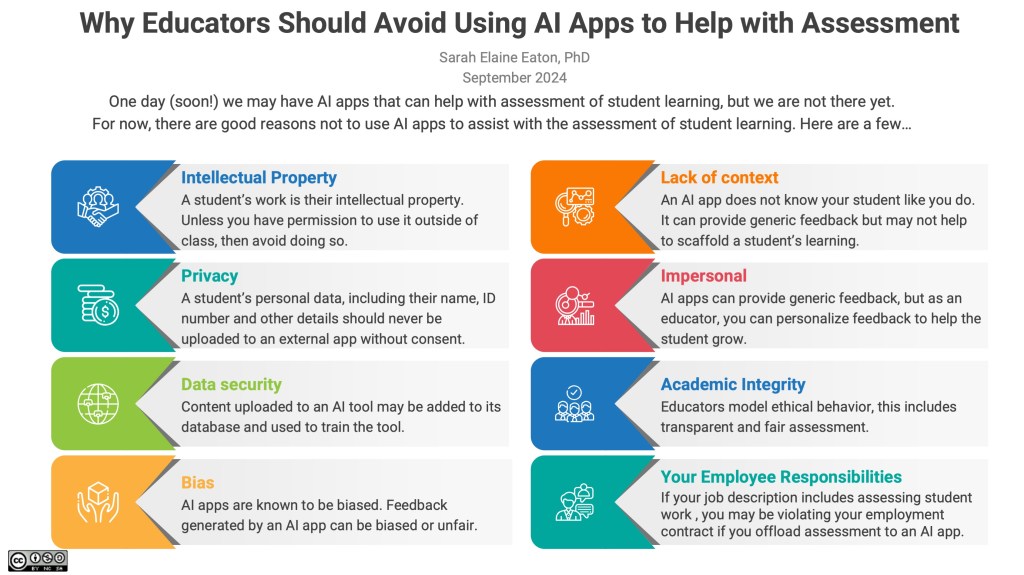

8 Tips on Why Educators Should Avoid Using AI Apps to Help with Assessment of Student Learning

Intellectual Property

In Canada at least, a student’s work is their intellectual property. Unless you have permission to use it outside of class, then avoid doing so. The bottom line here is that student’s intellectual work is not yours to share to a large-language model (LLM) or any other third party application, with out their knowledge and consent.

Privacy

A student’s personal data, including their name, ID number and other details should never be uploaded to an external app without consent. One reason for this blog post is to respond to stories I am hearing about educators uploading entire student essays or assignments, including the cover page with all the identifying information, to a third-party GenAI app.

Data security

Content uploaded to an AI tool may be added to its database and used to train the tool. Uploading student assignments to GenAI apps for feedback poses several data security risks. These include potential breaches of data storage systems, privacy violations through sharing sensitive student information, and intellectual property concerns. Inadequate access controls or encryption could allow unauthorized access to student work.

AI model vulnerabilities might enable data extraction, while unintended leakage could occur through the AI app’s responses. If the educator’s account is compromised, it could expose all of the uploaded assignments. The app’s policies may permit third-party data sharing, and long-term data persistence in backups or training sets could extend the risk timeline. Also, there may be legal and regulatory issues around sharing student data, especially for minors, without proper consent.

Bias

AI apps are known to be biased. Feedback generated by an AI app can be biased, unfair, and even racist. To learn more check out this article published in Nature. AI models can perpetuate existing biases present in their training data, which may not represent diverse student populations adequately. Apps might favour certain writing styles (e.g., standard American English), cultural references, or modes of expression, disadvantaging students from different backgrounds.

Furthermore, the AI’s feedback could be inconsistent across similar submissions or fail to account for individual student progress and needs. Additionally, the app may not fully grasp nuanced or creative approaches, leading to standardized feedback that discourages unique thinking.

Lack of context

An AI app does not know your student like you do. Although GenAI tools can offer quick assessments and feedback, they often lack the nuanced understanding of a student’s unique context, learning style, and emotional or physical well-being. Overreliance on AI-generated feedback might lead to generic responses, diminishing the personal connection and meaningful interaction that educators provide, which are vital for effective learning.

Impersonal

AI apps can provide generic feedback, but as an educator, you can personalize feedback to help the student grow. AI apps can provide generic feedback but may not help to scaffold a student’s learning. Personalized feedback is crucial, as it fosters individual student growth, enhances understanding, and encourages engagement with the material. Tailoring feedback to specific strengths and weaknesses helps students recognize their progress and areas needing improvement. In turn, this helps to build their confidence and motivation.

Academic Integrity

Educators model ethical behaviour, this includes transparent and fair assessment. If you are using tech tools to assess student learning, it is important to be transparent about it. In this post, I write more about how and why deceptive and covert assessment tactics are unacceptable.

Your Employee Responsibilities

If your job description includes assessing student work , you may be violating your employment contract if you offload assessment to an AI app.

Concluding Thoughts

Unless your employer has explicitly given you permission to use AI apps for assessing student work then, at least for now, consider providing feedback and assessment in the ways expected by your employer. If we do not want students to use AI apps to take shortcuts, then it is up to us as educators to model the behavior we expect from students.

I understand that educators have excessive and exhausting workloads. I appreciate that we have more items on our To Do Lists than is reasonable. I totally get it that we may look for shortcuts and ways to reduce our workload. The reality is that although Gen AI may have the capability to help with certain tasks, not all employers have endorsed their use in same way.

Not all institutions or schools have artificial intelligence policies or guideline, so when in doubt, ask your supervisor if you are not sure about the expectations. Again, there is a parallel here with student conduct. If we expect students to avoid using AI apps unless we make it explicit that it is OK, then the same goes for educators. Avoid using unauthorized tech tools for assessment without the boss knowing about it.

I am not suggesting that Gen AI apps don’t have the capability to assist with AI, but I am suggesting that many educational institutions have not yet approved the use of such apps for use in the workplace. Trust me, when there are Gen AI apps to help with the heaviest aspects of our workload as educators, I’ll be at the front of the line to use them. In the meantime, there’s a balance to be struck between what AI can do and what one’s employer may permit us to use AI for. It’s important to know the difference — and to protect your livelihood.

Related post:

The Use of AI-Detection Tools in the Assessment of Student Work – https://drsaraheaton.wordpress.com/2023/05/06/the-use-of-ai-detection-tools-in-the-assessment-of-student-work/

____________________________

Share this post:

Ethical Reasons to Avoid Using AI Apps for Student Assessment – https://drsaraheaton.com/2024/09/10/ethical-reasons-to-avoid-using-ai-apps-for-student-assessment/

This blog has had over 3.6 million views thanks to readers like you. If you enjoyed this post, please “like” it or share it on social media. Thanks!

Sarah Elaine Eaton, PhD, is a faculty member in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary, Canada. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of my employer.

Sarah Elaine Eaton, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, International Journal for Educational Integrity

Posted by Sarah Elaine Eaton, Ph.D.

Posted by Sarah Elaine Eaton, Ph.D.

You must be logged in to post a comment.