Join us for an innovative speaker series exploring how artificial intelligence is transforming education, academic integrity, and the future of learning. The 2025-2026 Postplagiarism Speaker Series brings together leading researchers and educators from around the world to examine how we can navigate the integration of AI tools in educational settings while maintaining ethical standards and fostering authentic learning. This series is hosted by the Centre for Artificial Intelligence Ethics, Literacy, and Integrity (CAIELI), University of Calgary.

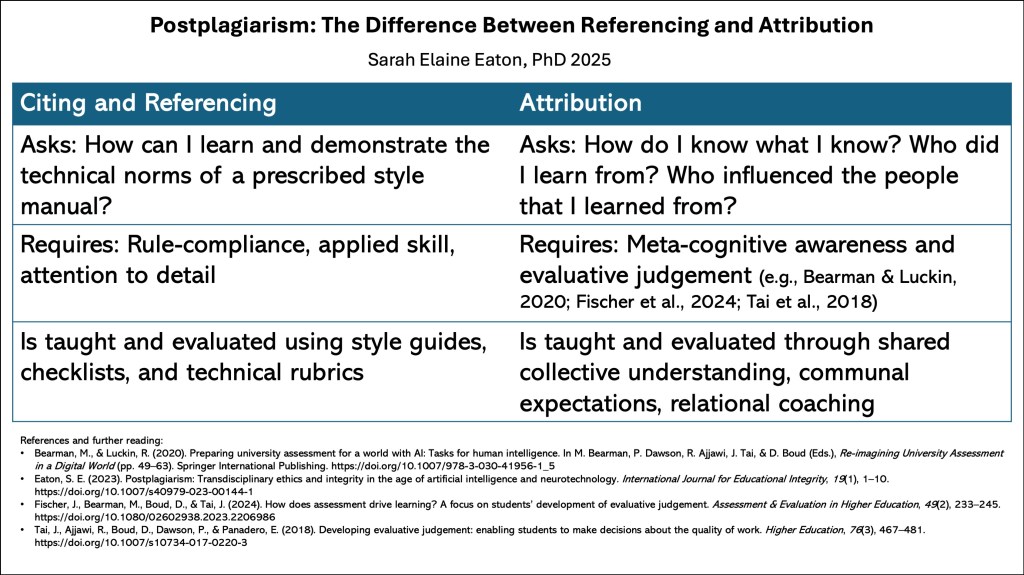

What is Postplagiarism? Postplagiarism (Eaton, 2023) refers to our current era where artificial intelligence has become part of everyday life, fundamentally changing how we teach, learn, and create. Rather than viewing AI as a threat to academic integrity, the postplagiarism framework offers practical approaches for embracing AI as a collaborative tool while preserving the values of authentic learning and ethical scholarship.

Series Highlights: This multi-part series features international experts who will share research-based insights and practical strategies for educators, administrators, and policymakers. Topics include foundational concepts of postplagiarism, assessment redesign, policy development, and innovative teaching approaches that prepare students for an AI-integrated world.

Who Should Attend:

- Faculty and instructors across all disciplines

- Educational administrators and policymakers

- Graduate students in education

- Academic integrity professionals

- Anyone interested in the future of education and AI

Format: Each session combines research presentations with practical applications, offering attendees actionable insights they can implement in their own educational contexts. Sessions are hybrid so participants can attend either in person or online. Sessions are open to the public and free for everyone to attend.

The series showcases the groundbreaking postplagiarism framework developed at the University of Calgary, which has gained international recognition and been translated into multiple languages. Participants will gain cutting-edge knowledge about navigating the challenges and opportunities of generative AI in education.

Time: All sessions are held 12:00 p.m. (noon) to 13:00 Mountain time. Please convert to your local time zone.

Session 1 : Postplagiarism Fundamentals: Integrity and Ethics in the Age of GenAI

Date: September 17, 2025

Description: Join us to learn about the award-winning postplagiarism framework that has been translated into half a dozen languages and has received worldwide attention. Postplagiarism refers to an era in human society in which artificial intelligence is part of everyday life, including how we teach, learn, and interact daily. (Eaton, 2023). Learn more about the six tenets of postplagiarism and how you can apply them to support students’ success.

Speaker: Dr. Sarah Elaine Eaton, University of Calgary

Bio: Sarah Elaine Eaton is a Werklund Research Professor at the University of Calgary. She researches academic integrity and ethics in educational contexts. Her work on postplagiarism marks her most important contribution to research, pedagogy and advocacy.

Check out the recording here.

Get a copy of the slides here.

Session 2: Smart or Shallow? Postplagiarism, Trust, and the Future of Learning with GenAI

Date: October 1, 2025

Description: In the postplagiarism era, GenAI compels educators to confront a fundamental choice: should it be trusted as a complementary tool that enhances learning, or as a competitive tool that undermines it? This talk explores how cognitive and affective trust explain the differences among student, educator, and employer perspectives on AI’s role in education. Drawing on David C. Krakauer’s distinction between cognitive artifacts, Kumar argues that academic integrity now requires more than attribution or authorship. It requires deliberate pedagogical practices that guide learners to use AI in ways that enhance, rather than diminish, human intelligence.

Speaker: Dr. Rahul Kumar, Brock University

Bio: Dr. Rahul Kumar is an Assistant Professor, Department of Educational Studies, Brock University. In his research he focuses on the disruptive force of GenAI on education. Its effect on academic integrity and how to cope with it. Though most of his work has focused on higher education, he has also undertaken research projects on how secondary school teachers are dealing with GenAI in their classrooms and schools.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3939984

Session 3: Assessment in a Postplagiarism era: The AI Assessment Scale as a framework for academic integrity in an AI transformed world

Date: October 15, 2025

Description: Developments in Generative AI are leading us closer to the concept of ‘postplagiriaism’, with traditional concepts of academic integrity being fundamentally challenged by these technologies. This lecture explores how the AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) offers a pragmatic response to this upcoming paradigm shift, moving beyond futile attempts at AI detection towards thoughtful assessment redesign. In a world where AI-generated content is becoming indistinguishable from human work, the AIAS (Perkins et al., 2024) provides a five-level framework that acknowledges this new reality whilst maintaining academic authenticity.

Rather than treating AI as a threat to be policed, the AIAS embraces it as a tool to be thoughtfully integrated where appropriate. From ‘No AI’ assessments that preserve foundational skill development, to ‘AI Exploration’ tasks that prepare students for an AI-saturated workplace, this framework offers educators practical strategies for the postplagiarism landscape. This talk will demonstrate how institutions can move from an adversarial ‘catch and punish’ mentality to a collaborative approach that recognises both learning integrity and technological advancement. The session will challenge traditional academic integrity paradigms and offer actionable insights for this new era of university assessment.

Speaker: Dr. Mike Perkins, British University Vietnam

Bio: Dr. Mike Perkins heads the Centre for Research & Innovation at British University Vietnam, Hanoi. He is an Associate Professor and leads GenAI policy integration and trains Vietnamese educators and policymakers on this topic. Mike is one of the authors of the AI Assessment Scale, which has been adopted across more than 250 schools and universities worldwide, and translated into 20+ languages. His research focuses on GenAI’s impact on education, and has explored various areas within this field. This has included AI text detectors, attitudes to AI technologies, and the ethical integration of AI in assessments through the AI Assessment Scale. His work bridges technology, education, and academic integrity.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3925369

Session 4: Designing for Integrity: Learning and Assessment in the Postplagiarism Era

Date: November 19, 2025

Description: In the postplagiarism era, where generative AI and related technologies are embedded in how ideas are produced and shared, academic integrity must be reimagined. Rather than treating plagiarism as a violation to be detected and punished, integrity becomes something to be intentionally cultivated through the design of both learning and assessment. This talk will explore how postplagiarism challenges traditional notions of authorship, originality, and attribution, inviting educators to move beyond rule enforcement toward fostering creativity, responsibility, and agency. I will discuss how aligning learning activities with authentic, meaningful assessment can reduce plagiarism incentives while preparing students for ethical participation in a world where human and AI contributions are intertwined. Participants will be encouraged to rethink not just how we assess, but why—and to envision integrity as a shared, evolving value in the age of AI.

Speaker: Dr. Soroush Sabbaghan, University of Calgary

Bio: Dr. Soroush Sabbaghan is an Associate Professor and the Educational Leader in Residence in Generative AI at the University of Calgary’s Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning. His work centres on human-centred design and the creation of human–AI collaborative environments, exploring the ethical, theoretical, and pedagogical implications of generative AI across K–12 and higher education. Drawing on research, teaching, and international collaborations, he examines how AI is reshaping notions of authorship, originality, and scholarly practice. Soroush is the editor of Navigating Generative AI in Higher Education: Ethical, Theoretical and Practical Perspectives, a collection that invites educators to critically engage with AI while maintaining care, dignity, and agency as core values. In his work, he encourages institutions to move beyond compliance-based approaches toward fostering creativity, responsibility, and adaptability in a hybrid human–AI world—principles that are at the heart of the postplagiarism era.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3939986

Session 5: Teaching Postplagiarism Tenets Through AI-Enhanced Creative Problem-Solving Model

Date: January 14, 2026

Description: While the concept of postplagiarism has gained increasing attention in the past two years, much of the discussion remains focused on writing tasks, leaving a gap in understanding how this framework applies to broader creative processes. Even less focus has been placed on strategies for teaching its tenets. This presentation bridges that gap by applying the Creative Problem Solving (CPS) model, enhanced with narrow AI tools such as chatbots, to explore how postplagiarism can be taught and understood in diverse creative contexts. By mapping the stages of CPS to postplagiarism’s key tenets, the session reveals nuanced connections between the two frameworks and offers what may be one of the earliest structured models for explaining current human–AI co-creation practices.

Speaker: Fuat Ramazanov, Acsenda School of Management

Bio: Fuat Ramazanov is the Program Director at Acsenda School of Management and a doctoral student at the University of Calgary. His doctoral research examines undergraduate students’ perceptions of the interplay between human and AI creativity throughout the creative process. A strong advocate for teaching for creativity, Fuat promotes approaches that cultivate creative thinking skills in students. His interests include innovative approaches to teaching, pedagogy in the age of AI, and the theory and application of postplagiarism framework.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3939987

Session 6: From Policy to Practice: A Postplagiarism Readiness Framework for AI Integration in Higher Education

Date: January 28, 2026

Description: This workshop introduces a readiness framework based on the six tenets of postplagiarism to critically assess institutional policies guiding faculty in using generative artificial intelligence. Participants will explore how the framework can be applied as a diagnostic tool to evaluate whether existing policies provide sufficient guidance, identify gaps, and support ethical, transparent, and future-ready integration of AI into teaching and learning. The session will combine conceptual grounding with practical analysis, offering participants strategies to strengthen policy and practice alignment in the age of AI.

Speaker: Dr. Beatriz Moya, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

Bio: Dr. Beatriz Moya is an assistant professor at the Institute of Applied Ethics and the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago, Chile. In her research she focuses on the intersection of academic integrity, educational leadership, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL).

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3939988

Session 7: A Transformative Model for Learning Academic Integrity in the Postplagiarism Era

Date: February 11, 2026

Description: The Postplagiarism framework has gained considerable attention, reshaping the landscape of academic integrity and ethical decision-making in education and research. This paradigm shift encourages educators to embrace the potential of artificial intelligence integration in transforming the competencies students need for their careers and communities. In this presentation I focus on two of the postplagiarism tenets: enhanced human creativity and the disappearance of language barriers. I will showcase preliminary findings of my doctoral research on academic integrity. As we recognize students’ diversity, these two postplagiarism-tenets provide a framework for fostering creative communication and accessible educational environments while disappearing potential obstacles within a transformative model for learning academic integrity.

Speaker: Bibek Dahal, MPhil, University of Calgary

Bio: Bibek Dahal, MPhil is a PhD Candidate in higher education leadership, policy, and governance at the Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Canada. Bridging Southern epistemologies and justice-centered transformative research, his scholarship focuses on academic integrity and ethics in global higher education. His doctoral study investigates a transformative model for learning academic integrity in international higher education.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3945787

Session 8: Designing Authentic Assessment in the PostPlagiarism GenAI Era: Making Judgement Visible

Date: February 25, 2026

Description: GenAI shifts academic integrity from detection to design by asking educators to assign work only students can do. Aimed at educators, this workshop presents the 3Cs framework (construct, collaborate, create), developed in secondary classrooms and adapted for teacher education. Sharma will introduce amplified intelligence as a lens and centre capability-agnostic design so tasks remain valid as GenAI tools evolve. Practice is anchored in six postplagiarism tenets: hybrid human and AI writing becomes normal, creativity is enhanced, language barriers diminish, control may be delegated but responsibility cannot, attribution remains important, and definitions of plagiarism are evolving. Participants examine how purpose sets permissions for GenAI use and translate that stance into prompts, checkpoints, and reflections that make process as visible as product. Classroom-tested examples provide assessment patterns and syllabus language for disclosure, verification, and boundaries. Outcomes: visible judgement, honoured student agency, reduced outsourcing.

Speaker: Dr. Sunaina Sharma, Assistant Professor, Brock University

Bio: Dr. Sunaina Sharma, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Educational Studies at Brock University, Ontario, Canada, specializing in secondary education and curriculum development. With 23 years of experience as a secondary teacher and 10 years as a program leader, she is deeply committed to creating a space for secondary students and educators to share their voices. Her recent research examines Ontario secondary school teachers’ responses to the proliferation of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), focusing on their questions, concerns, and instructional needs. Dr. Sharma’s research on digital technology and student engagement underscores that engagement arises not from the digital tools themselves but from students’ ability to construct knowledge through their use. Her work contributes to ethical GenAI adoption and advances effective pedagogical practices in educational settings.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3945789

Session 9: The SETA Framework for Integrity Education in the Postplagiarism Era

Date: March 4, 2026

Description: Technological Innovations are fuelling the call for changes in how students are taught and evaluated at all levels of the system. One visible change is a new focus on academic integrity, as the use of generative AI tools such as large language models (LLMs) have rendered the traditional discourse regarding plagiarism as obsolete, inadequate for the new environment. This presentation focuses on the support, education for integrity, teaching and learning, and assessment (SETA) framework. It identifies the various elements that are necessary in educating students for academic integrity within the GenAI-enabled environment. It focuses on the role of policies and their importance in creating the context within which academic integrity education takes place, and includes the punitive element which is necessary in instances where students choose to act contrary to the requirements of the academy. This discussion includes data gathered from students and librarians who participated in a 20 hour training for the development of academic integrity from across the Caribbean.

Speaker: Dr. Ruth Baker-Gardner, University of the West Indies, Jamaica

Bio: Dr. Ruth Baker-Gardner is the foremost voice on academic integrity in the Caribbean. She is a lecturer in librarianship at the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus in Jamaica. Dr. Baker-Gardner is author of Academic Integrity in the Caribbean which was awarded the Principal’s Research Award for outstanding Publication in the Book Category. She was also awarded the International Center for Academic Integrity Exemplar for Academic Integrity Award and the European Network for Academic Integrity Outstanding Researcher Award. Her latest publication Academic Integrity meets Artificial Intelligence, the Case of the Anglophone Caribbean, examines the region’s readiness for artificial intelligence use by examining its academic integrity structures and practices.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3945790

Session 10: Postplagiarism Perspectives: Comparative Insights from K-12 and Postsecondary Research

Date: March 18, 2026

Description: As generative AI technologies reshape educational landscapes, academic integrity must be reconceptualized across both K–12 and postsecondary contexts. Drawing from two doctoral research studies, this presentation explores the complex interplay between technological adoption, ethical formation, and institutional change.

The first study examines K–12 administrators navigating pedagogical and ethical uncertainties introduced by human-AI collaboration. Employing the Technology Acceptance Model, Innovation Diffusion Theory, and the 4M Framework, this research explores how administrators balance AI integration with pedagogical values during ‘AI arbitrage’, the liminal space where early adopting students outpace institutional adaptation.

The second study explores how CPA-accredited accounting programs embed ethical competencies through assessment, particularly regarding AI-enabled misconduct. Employing Rest’s Four-Component Model of Morality, Biggs’ Constructive Alignment, and an Integrity–Assessment Alignment Matrix, this research examines professional ethics education amid technological disruption.

Together, anchored in Eaton’s postplagiarism concept, these complementary theoretical lenses provide comprehensive analytical approaches to understanding educational transformation across the learning continuum.

Speakers: Naomi Paisley & Myke Healy

Bio: Naomi Paisley is a Chartered Professional Accountant (CPA) with over 20 years of experience in accounting, audit, and taxation. She currently teaches at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT), where she develops and delivers curriculum in financial reporting, assurance, and Canadian tax. Naomi is also a co-author of nationally adopted Canadian auditing and accounting textbooks and collaborates on the integration of evolving standards, DEI, ESG, and Indigenous perspectives in accounting education. As a doctoral candidate in the EdD program at the University of Calgary’s Werklund School of Education, her research explores how CPA-accredited undergraduate accounting programs prepare students for ethical challenges in the profession, particularly considering AI-enabled misconduct. Her study uses Rest’s Four-Component Model of Morality and Biggs’ Constructive Alignment to analyze ethics education and assessment practices in accounting programs. Naomi’s work supports the alignment of academic integrity initiatives with the expectations of the accounting profession and CPA Canada.

Myke Healy is an educational leader with over 20 years of experience in K-12 teaching and administration. He currently serves as Assistant Head – Teaching & Learning at Trinity College School, where he leads academic strategy and faculty development. Myke holds an M.Ed. in assessment and evaluation from Queen’s University and annually facilitates AI-focused modules at the Canadian Accredited Independent Schools (CAIS) Leadership Institute. As a doctoral candidate in the EdD program at the University of Calgary’s Werklund School of Education, his research examines how K-12 administrators navigate generative AI and academic integrity challenges during technological adoption. His study uses the Technology Acceptance Model, Innovation Diffusion Theory, and the 4M Framework to analyze AI integration and postplagiarism concepts in secondary education. Myke presents nationally and internationally on AI in education and serves on the Ontario College of Teachers’ accreditation roster, the board of eLearning Consortium Canada, and instructs leadership and assessment courses at Queen’s University.

Register here: https://workrooms.ucalgary.ca/event/3945792

______________

Share this post: 2025 – 2026 Postplagiarism Speaker Series: Navigating AI in Education – https://drsaraheaton.com/2025/09/26/2025-2026-postplagiarism-speaker-series-navigating-ai-in-education/

Sarah Elaine Eaton, PhD, is a Professor and Research Chair in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary, Canada. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of my employer.

Posted by Sarah Elaine Eaton, Ph.D.

Posted by Sarah Elaine Eaton, Ph.D.

You must be logged in to post a comment.