In a recent talk I did at the University of Toronto Mississauga, I was chatting with a couple of folks afterwards and they asked if one specific slide was available as an infographic. It wasn’t and I promised to follow up. (This blog post is for you Amanda and Victoria!)

Artificial intelligence tools can generate human-like text and knowledge creation has become increasingly collaborative, questions arise about traditional academic practices. Although many conventions are being reimagined, citing, referencing, and attribution remain important. Attribution — acknowledging those who have shaped our thinking—transcends the mechanical act of citing sources according to prescribed formats. It represents an ethical commitment to intellectual honesty and respect (Eaton, 2023).

Attribution is a cornerstone of the postplagiarism framework. In the postplagiarism era, where the boundaries between human and AI-generated content blur and traditional definitions of authorship are challenged, the practice of acknowledging our intellectual influences becomes more vital, not less (Kumar, 2025). Attribution serves multiple purposes: it honors those who contributed to knowledge development, establishes credibility for the writer, and allows readers to explore foundational ideas more deeply.

Many educators and students mistakenly equate attribution with the technical minutiae of citation styles. I am talking here about the precise placement of commas, periods, and parentheses. While these conventions serve practical purposes in academic writing, they represent only the surface of what attribution entails (Gladue & Poitras Pratt, 2024). At its core, attribution demands that we answer questions such as: How do I know what I know? Who were my teachers? Whose ideas have influenced my thinking?

In this post (a re-blog from the postplagiarism site) I explore attribution as an enduring ethical principle within the postplagiarism framework. We’ll distinguish between citation as mechanical practice and attribution as intellectual honesty, examine how attribution practices might evolve with technology, and consider how we might teach attribution as a value rather than merely a skill (Eaton, 2024). Throughout, we’ll keep returning to a central idea: even as definitions of plagiarism transform, the need to recognize and pay respect to those from whom we have learned remains constant.

Attribution vs. Citation: Understanding the Differences

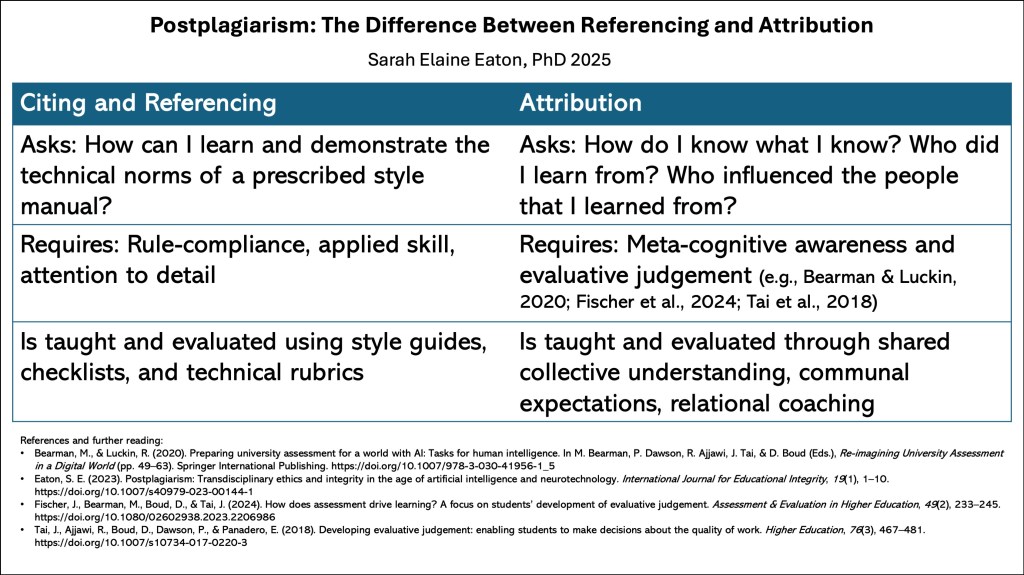

Understanding the distinction between attribution and referencing is crucial in our discussion of academic integrity in a postplagiarism era. The terms ‘referencing’ and ‘attribution’ are often used interchangeably, but they represent fundamentally different approaches to giving credit where it is due. In the table below, I present an overview of some of the differences.

Table 1

Attribution versus Referencing

Citing and Referencing

First, let’s talk about citing and referencing. Citing is often referred to in-text citation. In APA format, for example, we cite sources in the main body of the text as we write. Then, we produce a list of references, usually with the heading “References” at the end of the paper. (I have modelled this practice throughout). If we follow APA, the sources cited in the body of the text should exactly match the sources in the reference list at the end, and vice versa. So, citing and referencing go hand-in-hand. For the purposes of this post, I’ll use the term ‘referencing’ collectively to refer to both citing and referencing, given that the two are intertwined.

A foundational question about referencing is: How can I learn and demonstrate the technical norms of a prescribed style manual?

Let me give you an example of what I mean. I did my undergraduate and master’s degrees in literature. We used the Modern Language Association (MLA) style guide. When I moved over to Education to undertake my PhD, I had to learn a completely different style, the one prescribed by the American Psychological Association (APA), as that is the style used across much of the social sciences. I often describe having to shift from learning MLA style to APA style as intellectual trauma. I had spent years meticulously learning to be rule-compliant to MLA style. I knew the details of MLA style inside and out. Having to learn APA style meant unlearning everything I’d spent years learning about MLA style. My PhD supervisor marked up drafts of my work with a red pen, noting APA errors everywhere.

I bought the APA style guide (we were using the 5th edition back then) and set out to memorize every detail to ensure that I knew the rules. Citing and referencing are taught and evaluated using style guides, checklists, and technical rubrics to evaluate how well someone has followed the rules. Citing and referencing are essentially about rule compliance.

Attribution

Attribution goes beyond the technical aspects of rule compliance. When we give attribution, we dig deeper into questions about our intellectual lineage. We ask: How do I know what I know? Who did I learn from? Who influenced the those from whom I have learned?

Attribution requires meta-cognitive awareness and evaluative judgement. If you are unfamiliar with these concepts, I recommend the work of Bearman and Luckin (2020), Fischer et al. (2024), and Tai et al. (2018). Collectively, they explain evaluative judgement and meta-cognitive awareness better than I ever could.

(If you’re paying attention, you’ll see that I just combined citing with attribution there… I provided the sources as per the citing rules of APA, and I also talked about how I learned about deeper concepts from some terrific folks who have done deep work on the topic. See, you can combine citing and referencing with attribution. It’s not all or nothing.)

We teach attribution through a shared collective understanding, by establishing communal expectations and through (often informal) relational coaching.

In everyday conversations, we often reference where we learned ideas. We say, “As my grandmother always said…” or “I read in an article that…” These informal attribution practices demonstrate how instinctively we connect ideas to their sources. Citing and referencing formalizes socialized practices that have extended across various cultures for centuries.

When we give attribution, we show gratitude for the conversations, texts, and teachings that have formed our understanding. This perspective shifts attribution from a defensive practice (avoiding plagiarism accusations) to an affirmative one (acknowledging the intellectual debt we owe to others who have generously shared their knowledge with us).

Acknowledging Others’ Work in the Age of GenAI

Generative AI tools have disrupted our traditional understandings of authorship and attribution. These technologies create new questions about intellectual ownership and acknowledgment practices that our citing and referencing systems weren’t designed to address. GenAI models produce outputs based on massive training datasets containing human-created works. When a student uses ChatGPT to draft an essay, the resulting text represents a complex blend of sources that even the AI developers cannot fully trace. This opacity challenges our ability to attribute ideas to their original creators (Kumar, 2025).

The collaborative nature of AI-assisted writing further blurs authorship boundaries. Who deserves credit when a human prompts, edits, and refines AI-generated text? The distinction between tool and co-creator is difficult to establish. This is another tenet in the postplagiarism framework.

In work led by my colleague, Dr. Soroush Sabbagan, we found graduate students wanted agency in how they integrate AI tools while maintaining academic integrity (Sabbaghan and Eaton (2025). The graduate students who participated in our study, “Participants also emphasized the importance of combining their own expertise and judgment with the AI’s suggestions to create truly original research.” (Sabbaghan & Eaton, 2025, p. 18).

The postplagiarism framework offers helpful guidance by distinguishing between control and responsibility. Although students may share control with AI tools, they retain full responsibility for the integrity of their work, including proper attribution of all sources, both human and machine. Ultimately, the goal isn’t to prevent AI use but to cultivate ethical practices for learning, working, and living.

As Corbin et al (2025) have noted, AI presents wicked problems when it comes to assessment. I would extend their idea further by saying that AI presents wicked problems for plagiarism in general. There are no absolute definitions of plagiarism, but if we think about citing, referencing, and giving attribution as ways of preventing or mitigating plagiarism, then AI has certainly complicated everything. These are problems that we do not have all the answers to, but disentangling the difference between rule-based referencing and attribution as a social practice of paying our respects to those from whom we have learned, might be one step forward as we enter into a postplagiarism age.

The ideas I’ve shared here are not intended to be exhaustive, but rather to help folks make sense of some key differences between referencing and giving attribution and to recognize that citing and referencing are deeply connected to rule compliance and technical rules, whereas giving attribution can at times be imprecise, but may in fact be more deeply-rooted in a desire to give respect where it is due.

As I have tried to model above, it does not have to be all or nothing. Referencing can exist in the absence of any desire to respect others for the work they have created and attribution can be given orally or in any variety of ways that may not comply with a technical style guide. When we are working with students, it can be helpful to unpack the differences and talk about why both are need in academic environments.

There is more to say on this topic, but I’ll wrap up here for now. Thanks again to Amanda and Victoria, who nudged me to write down and share ideas that I have been talking about for a few years now.

References

Bearman, M., & Luckin, R. (2020). Preparing university assessment for a world with AI: Tasks for human intelligence. In M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, & D. Boud (Eds.), Re-imagining University Assessment in a Digital World (pp. 49–63). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41956-1_5

Corbin, T., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Dawson, P. (2025). The wicked problem of AI and assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2553340

Eaton, S. E. (2023). Postplagiarism: Transdisciplinary ethics and integrity in the age of artificial intelligence and neurotechnology. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00144-1

Eaton, S. E. (2024). Decolonizing academic integrity: Knowledge caretaking as ethical practice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(7), 962-977. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2312918

Fischer, J., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Tai, J. (2024). How does assessment drive learning? A focus on students’ development of evaluative judgement. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(2), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2206986

Kumar, R. (2025). Understanding PSE students’ reactions to the postplagiarism concept: a quantitative analysis. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 21(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-025-00182-x

Sabbaghan, S., & Eaton, S. E. (2025). Navigating the ethical frontier: Graduate students’ experiences with generative AI-mediated scholarship. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-024-00454-6

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero, E. (2018). Developing evaluative judgement: enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education, 76(3), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3

Note: This is a re-blog. See the original post here:

Postplagiarism: Understanding the Difference Between Referencing and Giving Attribution – https://postplagiarism.com/2025/09/05/postplagiarism-understanding-the-difference-between-referencing-and-giving-attribution/

Posted by Sarah Elaine Eaton, Ph.D.

Posted by Sarah Elaine Eaton, Ph.D.  The other day I was talking with

The other day I was talking with  One strategy to improve the quality of your writing is to read it aloud. I’ve been doing this for years.

One strategy to improve the quality of your writing is to read it aloud. I’ve been doing this for years.

You must be logged in to post a comment.